Keeping up with my quest on exploring probabilistic data structures, today I am going to present you Bloom filters, an ingenious idea that allows us to quickly verify membership within a set.

As usual, I sound awful when using grown-up words: filters? Membership? Verification? Just bear with me for a few minutes as we’re about to delve into one of the most ingenious ideas in the world of computer science, one that was born almost 50 years ago.

Who invited this guy?!?

If you remember my recent post on HyperLogLog and the cardinality-estimation problem, there I introduced Tommy, a friend of mine that joins me at meetups and conferences.

Today Tommy and I are extremely busy trying to organize an invite-only hackathon for the best developers in the area: we recently setup a website with sign ups capped at 100 people, and have just reached the venue with a printed list of people who have made it through.

Unfortunately, since we have limited space at the venue, we need to make sure that each and every person who wants to come in signed up online and, if not, we unfortunately have to turn them down. Armed with a list of names, Tommy starts processing each and everyone while I take care of setting up the rooms and so on:

Hi there, I am Tommy! Did you by any chance sign up online? What is your name?

Yeah man, I definitely did! Why do you need my name?

Unfortunately we only have seats and food for 100 people, so we can’t let

everyone in. Let me just check if your name is on the list…

Ok man, no problem…name’s Greg Sestero!

…mmm…

Is there any problem?

…mmm…

…hello?

Damn Greg, give me some time! I have to go through 100 names to find yours!

Quickly, Tommy realizes that this is going to take him too long, so he comes over and starts telling me that we need to find another way to figure out whether people have signed up or not: with hundreds of people in front of him, he can’t go over the list for each and everyone of them!

Alex, man…I can’t go over the list for each and everyone out there. We need to

find a way to check if these people signed up way faster than this, as it’s taking

me too long! At this pace, we’ll start the hackathon in 2 hours!Even if it’s not 100% accurate, we need to find another method of processing

each and everyone…at the end of the day we don’t care if we let in 98 or 106 people,

but we need to do it real quick!

Tommy, we can’t turn people down if they subscribed, I’d be pretty pissed if that

happened to me! We should let everyone who subscribed in, and maybe have some

false positives so that a couple people who didn’t subscribe make it in…but again,

there’s no way we can deny entry to people who actually subscribed!

So, false positives are ok but false negatives aren’t…I think I’ve got this!

Tell me Tommy, what are you thinking about?

You remember in our signup form we asked people for their birthday? Can you quickly

print me a list of all years, months and days people were born in? It should look like:YEAR

1978

1979

1984

1985

1986

…MONTH

01

03

04

05

07

…DAY

01

02

09

10

11

12

15

17

…I’m gonna ask people what year they were born.

If it’s in the list, I’m going to ask them what month.

If it’s in the list, I’m going to ask them what day.If they’re all in the list, there’s a good chance these guys signed up! We will

definitely have false positives, but I don’t have to go through a list of 100 names,

just, maybe, 20 years, 10 months and 20 days…it’s still half of the original list

of names!

You’re a genius! Not an exact science but we should be able to get this going!

Bloom filters work a little bit differently, but the idea behind them is quite similar to the one I just presented — let’s get more technical!

The technical bits…

…because we’re literally talking about bits! Instead of birth dates, a Bloom filter simply uses a bit array such as:

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|---|

Now, like in a regular set, let’s start adding elements to the filter: we first need to pick a hashing function (like murmur) and then flip a bit to 1 when the hashing function returns the index of such bit.

For example, the string some_test would return 2 in an evenly distributed murmur

(you can test it here), so we flip the element

at index 2:

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|---|

Let’s add another element to the filter — another_test hashes to 4:

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|---|

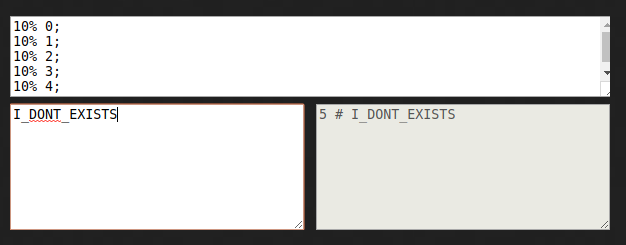

And now let’s test the bloom filter! Is I_DONT_EXISTS in the filter?

Taken from murmurhash.shorelabs.com:

This element hashes to 5, and the value of the element at index 5 in our

filter is 0. This means that the element is not in the original set.

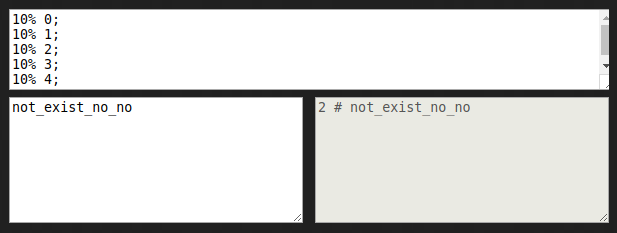

Let’s do another test? Let’s see if not_exist_no_no is in the filter:

This element hashes to 2, and the value of the element at index 2 in our

filter is 1. This would suggest that the element was in our original set —

here’s where Bloom filters trick you.

A Bloom filter guarantees certainty when it tells you an element is not in a set, but can only give you a probability of whether the element was in it. This means that you can reliably use these filters to exclude values from a set, but are not going to be 100% sure they are in the set if the filter returns a positive result — in other words: Bloom filters never give you false negatives, but can give you false positives.

If you’re still having some trouble to understand how they work (I’m not the best at this, I’ll admit it) I would strongly encourage you to have a look at this interactive explanation of Bloom filters.

Even MOAR technical bits!

Bloom filters are actually different — I tend to oversimplify for the sake of understanding. The two most important differences from the approach I explained above are that:

- the length of the bit array needs to be “quite” proportional (more on this later) to the number of elements in the original set, as a set with 100 elements represented in a filter with only 2 bits would be useless (there’s an incredibly strong chance both bits would be positive, increasing the chances of false positives)

- multiple hashing functions are used to increase entropy within the distribution of 1-value bits, as a single hashing function could lead to a higher number of collisions

There are generally four variables you want to keep an eye on when using a Bloom filter:

- the number of items in the filter (= number of items in the original set, n)

- the probability of false positives (p)

- number of bits in the filter (m)

- number of hash functions used to convert element into bits (k)

You start by knowing (or by having a good estimate of) your n and defining an acceptable p; at that point you derive m and k by:

m = ceil((n * log(p)) / log(1.0 / (pow(2.0, log(2.0)))))k = round(log(2.0) * m / n)

We can test this out by using this interesting calculator made available by Thomas Hurst:

| items (n) | probability (p) | space (m) | hash fn (k) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 0.5 | 145b | 1 |

| 100 | 0.1 | 480b | 3 |

| 1k | 0.5 | 175B | 1 |

| 1k | 0.1 | 600B | 3 |

| 1M | 0.1 | 600KB | 3 |

| 1M | 0.01 | 1.2MB | 7 |

| 1M | 0.001 | 1.7MB | 10 |

Now it’s the “show me some code!” time, so let’s grab the bloomfilter package on NPM and let’s run some benchmarks. We will first create a list of a 10k elements and check 1k random elements against it:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

and let’s try to compare it with a high-precision (0.01% probability of false positives) filter:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | |

For the lolz, let’s also have a very imprecise bloom filter thrown into the mix:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

…and let’s run them together:

1 2 3 | |

Quite of a difference! Such performance gains are quite understandable since the

filter does not need to loop through the set (O(n)), it just needs to hash the

element it has received as many times as the number of hash functions in the filter (O(k))

and then access the list at the index produced by the hash functions (O(1)), ending

up at a complexity of O(k) — which is pretty darn fast!

Another important thing to consider is, beside the time-advantage, is that the space advantage of Bloom filters is quite significant: since they don’t need to store the original elements of the set, but just a fixed-length bit sequence, they tend to consume less space than hash tables, tries or plain lists.

An interesting thing to consider is how these filters relate to hash tables:

hash tables gain a space and time advantage if they begin ignoring collisions and store only whether each bucket contains an entry; in this case, they have effectively become Bloom filters with k = 1

A note on hashing functions

It’s really important to pick the right hashing functions when implementing a Bloom filter, as they need to:

- be extremely fast: strong cryptographic hashing functions are not suitable since

they are generally computationally expensive (= slow), while you will want your

O(k)to be as fast as possible - distribute outputs uniformly: it’s important for the filter to “turn bits on” as uniformly as possible, as a “biased” hash function would end up increasing the probability of false positive

For example, a unanimous choice seems to be MurMurHash3, which guarantees a good degree of uniformity in terms of distribution and was designed with speed, not security, in mind.

Closing remarks

Have you ever visited a website and seen a security notice from your browser, telling you the URL you’re about to access could be malicious? How do you think your browser can efficiently check whether the URL is among a huge list of malicious ones?

Well, up until a few years ago Chrome used Bloom filters and that’s just one interesting, beneficial application of this amazingly clever data structure (if you’re curious, it since switched to prefix sets — “Searches take about 3x as long, but it should scale well”).

To give you some more context, Bloom filters appeared in July 1970 — that is 7 months into the unix timestamp.

Here I sit speechless.

Further readings

- the original paper

- What are Bloom filters (and how Medium uses them)?

- After Lambda: Exactly-once processing in Cloud Dataflow

- Sketching & Scaling: Bloom Filters

- Why Bloom filters work the way they do

- Probablistic Filters Visualized

- Cuckoo Filter: Practically Better Than Bloom

- Bloom Filters Explained